Sunday, August 19, 2007

Thoughts On Art And The Body

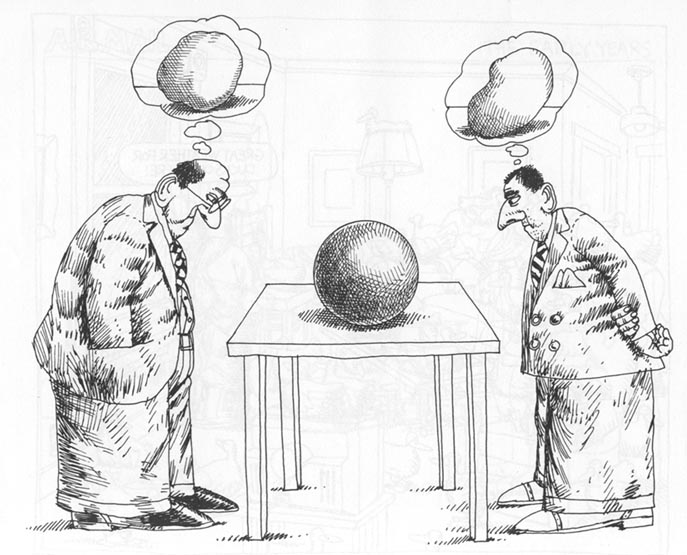

Here’s my question: do we forget ourselves when we’re moved by art?

A deeper question that motivates this is: what the hell is the nature of that artistic experience? Is there a single sort of ‘artistic experience’ that can cover the appreciation of all the arts, from dancing to poetry? Or are they all member of a broader class of experience? Or are they simply all called ‘art’ because of some linguistic misnomer, the same way whales were once thought of as fish? But we’re not going to get into that larger question right now.

I was thinking about this all last night at a mellow rock concert. All us kids were mustered around the stage, ignoring anything else that wasn’t held in the yellow and red gel-lights that flooded the small stage. Now, what I was thinking was that when we are moved by art, when we stare at the woman playing keyboard singing her heart out on the stage, we forget ourselves. We stop thinking of our own individual fabric of memory, thought, and body, and are somehow dissolved into something else – namely the artistic experience.

In Kant’s Third Critique I think we see a bit of this. Kant thought that all aesthetic judgments were universal, at least ideally; and that when we viewed art we did so disinterestedly – that is, ignoring the bias of personality. So when I look at a given work of art and call it trash, I don’t mean “Me, Brendan Mackie, who had a bad day today and is a white male in 2007 America, think that this work of art is a piece of trash” I mean “This piece of art is a piece of trash for everyone at any point in time” and implicitly “any dissenting opinion is a result of a failure of judgment or taste”. The disinterested viewer, the ideal viewer, will have the same reaction to a piece of art no matter who they are. It is up to the viewer of the art to get into the space in which they can filter out all the inessential quirks of their personal experience to experience something artistic that is somehow common to all people. (If anyone out there knows Kant better than me, and thinks that I’m butchering the Third Critique here, feel free to drop a comment about it – I haven’t read the damned thing in two years or so.)

But there’s something really unsatisfying about Kant’s view – especially my canned version of Kant’s viewed. Some of the pieces of art I love the most appeal to me not just because of their intrinsic universal value of the me as art objects but because of some personal value I can’t expect other people to share. I like Mirah, for instance, because I listened to her with a really good friend – and also, of course, because I think Mirah makes good music. Even if we partitioned off the personal pleasures of a given piece of art from the non-personal: thereby saying that the pleasure I get from my association of listening to Mirah is not an actual aesthetic pleasure, but more an aesthetic epiphenomena, limiting the aesthetic feeling to only those things that can be expected to be universal; that doesn’t solve the problem of cultural taste. We do not even need to look far beyond our own houses to see the tyranny of culture. My father, for instance, an open-minded and tasteful individual, cannot, for the life of him, understand much rap. But I can. Because I have been inculcated into how to listen to rap. Siilarly, I can’t understand modern dance to save my life and think that every piece of modern dance is a pile of pretentious poo. And while I might very well be right in thinking that, I’m open to the fact that I might not be able to appreciate good modern dance. To read a piece of art requires an understanding of a cultural grammar that we cannot expect to be universal. So we can’t expect our appreciation of art to be universal.

But we can ask a Kantian question and constrain it, and maybe then we come up with something worthwhile: if, without personal association and with the required cultural literacy, is there an essential universal quality to art?

Okay. So that’s just the set-up for my insight. I was wondering, as I watched all these people nodding along to the music last night, that we somehow forget our bodies when we are in the throes of the aesthetic experience. That we lose ourselves, our partictularness, in favor of a deeper, more universal connection to art.

Now I don’t know whether that’s an accurate description of what happens to us when we look at art, but I think that it points to the borders of the aesthetic experience. We have to be really careful when we’re talking about how people respond to art. There’s been an awful lot of ink and hot air thrown about what happens when a person looks at a painting or something and scratches their chin and calls it beautiful. I’d say that the only thing that the aestheticians can agree on is that the aesthetic experience is important. For some reason. Though I’ll be damned if anyone can agree why art is important.

So while I thought about this question, I kept on running into different questions that branched off that.

1) Can you experience art if you are a member of a marginalized minority group?

So much of English majordom is so obsessed by this question, and by the little questions that pop up around it – and I am frankly sick to death of it, and don’t think it leads us down any insightful avenues. So I will ignore it for now.

2) What about when you’re sick, or hungry, or tired – then can you have the aesthetic experience? And is it then diminished somehow?

3) And what about when you’re in a bad mood?

4) Is there are ‘right’ aesthetic experience to a given work? And a wrong one? If I say that Rhapsody in Blue makes we feel jaunty, and everyone else says it makes them feel profound – is my aesthetic experience wrong? Can you have a wrong aesthetic experience? What about an ignorant person who misread Huck Finn and thought that it was genuinely racist? What then?

5) Can we even adequately communicate the aesthetic experience? Or is it somehow beyond the grasp of our words? And if it is beyond the measurement of language – does it exist? I think of Wittgenstein, who argues that there can be no such thing as a private language, that there can be no such thind as words that refer only to individual things in our individual heads; and then I think of Einstein who said “Not everything that matters can be measured”.

6) Is the aesthetic experience even important at all?

Now, I have no answers to any of these questions. But if any of you out there have any – give them to me, I’d be interested to hear.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

The aesthetic experience seems to me like a drug. People make art to try and attain that same high achieved from their sense of a 'loss of self,' and people seem to want to experience art for the same reason. Maybe art exists because deep-down, people are slaves to this 'high' consciousness, and subsequent 'greater understanding of life/themselves'. A means to an end?

Google Book Search!

http://books.google.com/books?id=xB-niCZQ2SEC&dq=art+and+the+loss+of+self&pg=PA7&ots=2eDk9dVnSt&sig=qoABQYemMHgKL7i6o5-6OBs6Bgg&prev=http://www.google.com/search%3Fhl%3Den%26q%3Dart%2Band%2Bthe%2Bloss%2Bof%2Bself%26btnG%3DGoogle%2BSearch&sa=X&oi=print&ct=result&cd=2#PPP1,M1

I think that you're onto something there, mystery commenter - but I think maybe the order is reversed. I think that people's experience of drugs is so powerful because it mimics or stands in the same place as spiritual and aesthetic experience. There's so much hoopla out there about people having mystical experiences as a result of drug use. And I think maybe all of these experiences tap into a satisfying loss of self - and maybe we're just slaves to this experience in the same way we're slaves to satisfaction? That is, sure, we're addicted to it - but why wouldn't you want to be addicted to it?

Post a Comment